Library Stories

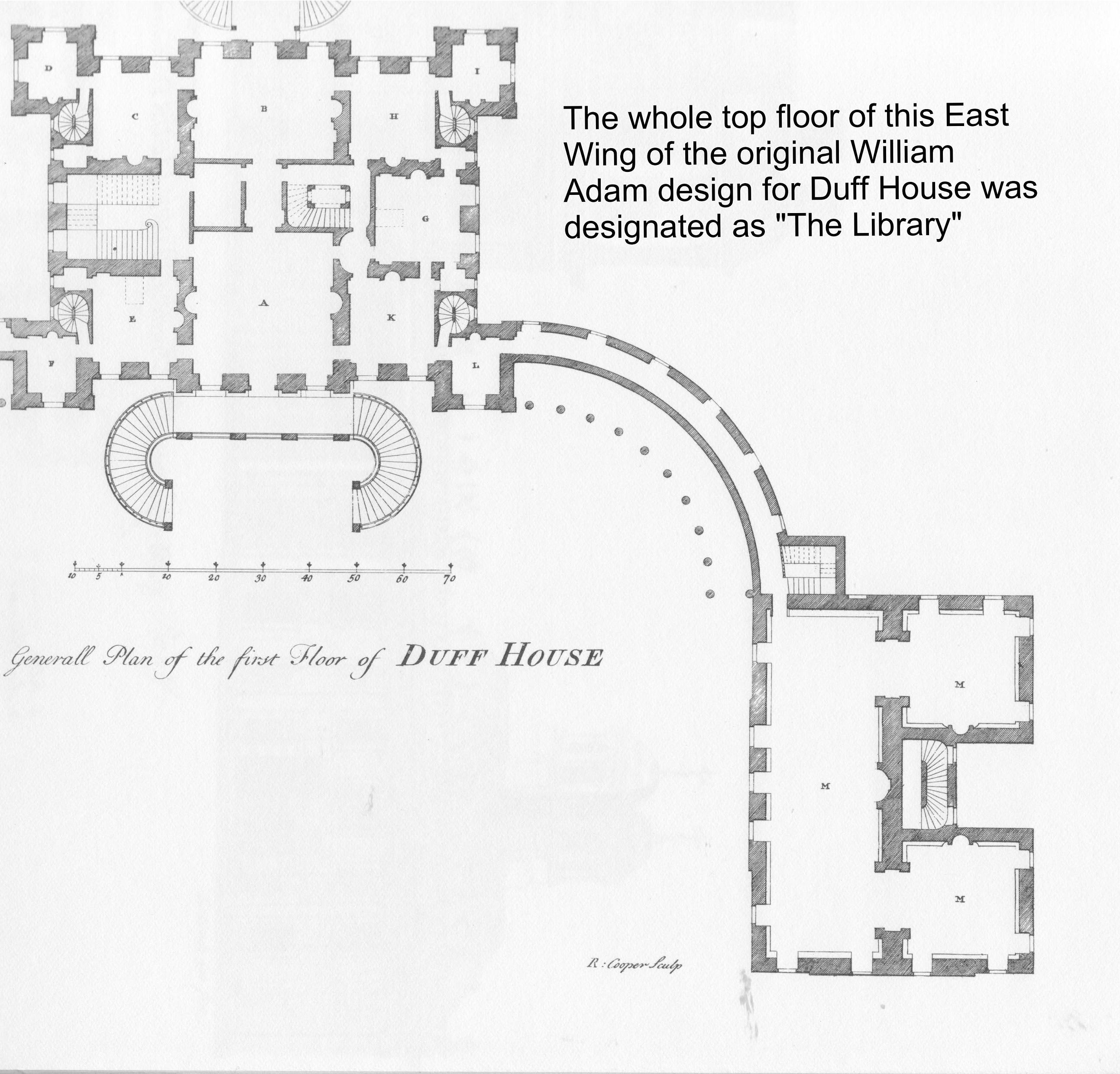

Duff House houses an extensive Library – part of the Dunimarle Collection. In recent years this has not generally been accessible to the public so regular “Stories” are published here to share some of the splendour of what is a really fine library. The Stories will share some of the background, details of some of the books, information about those that made the collection, their bookmarks, their scribbles – in fact anything and everything to do with the Library!

With many thanks to Historic Environment Scotland and the Trustees of the Erskine of Torrie Institution (SC002440) for their support for this project, and especially to Sandra Cumming for all her ideas and her direct contributions of several of the stories below. Many of the photos in these Stories have been taken by Sandra and her permission to use them is really appreciated.

++++++++++

18-Apr-23 SOUTH AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE – a piece of local history

Hiding within the Dunimarle Library are two books that represent the beginning of one small element within the history of Banff! The story is linked with Napoleon Bonaparte and his activities in Europe as he tried to assert the might of France; as well as the colonial ambitions of Great Britain.

Early in the eighteenth century, one of the parts of the world that was on the fringes of the developing economic prosperity, was that of South America. For centuries it had been part of Spanish colonialism, ruled by Spaniards, and the United Kingdom found it difficult to get a foothold, to try to take advantage of growing trade opportunities. After all, the Battle of Trafalgar had only taken place in 1805; diplomatic relations with Spain were poor.

But it also meant that Spain’s focus was on it’s home issues, and it’s grip on it’s South American colonies was slipping. Not only did Great Britain see this as an opportunity to grow it’s interest’s there (indeed in 1806 the UK started an invasion of the River Plate area), but it meant that the various South American states saw the possibility that they could think about independence.

And then, in 1808, Napoleon’s army entered Spain. This re-configured various alliances; Britain, thinking of it’s various opportunities, declared neutrality. This meant it could help whoever and wherever it felt there was an advantage for it.

One of the authors who was promoting the independence of South America called himself “William Burke”; in fact no-one knows for sure who he was and a number of theories have been put forward. He had published various South American histories and treatises, but specifically in 1807 he published “The Emancipation of South America; the Glory and Interest of England” [DH Lib 1121C]. The very fact that a copy of this book is part of the Dunimarle Library at Duff House is perhaps some evidence that this book – and a subsequent companion volume – Additional Reasons [DH LIB 1121D] – were widely read by the elite throughout the land, and therefore had an influence on the actions of the British Government. These books, published in London, found their way to Dunimarle in rural Fife, adding to the huge amount of coverage within the newspapers – at that time widely read by people at all levels of society. For example the Aberdeen Press and Journal seemed to have regular columns about the situation in South America for lots of the first quarter of the nineteenth century (the Banffshire Journal only started in 1845)!

And is all this South American history relevant to Banff and Duff House? Absolutely it is, and has been for two hundred years, and is specifically relevant in 2024.

One of the consequences of the Napoleon and UK’s independence stance, was that the UK sent troops to support Spain’s fight against Napoleon, and as a consequence of that, James Duff offered his services. He had been fighting elsewhere in Europe and was now a seasoned and capable soldier. He fought valiantly for Spain and was given a generalship. One of the people he fought alongside was José de San Martin – another experienced and capable soldier – and they formed a life-long friendship.

José was born, in 1778, in a small village, Yapeyu, on the west (Argentine side) of the River Paraguay, about 300 miles north of Buenos Aires; his father was a Spanish soldier cum administrator of the local province. The family moved to Spain arriving in 1784; José joined the Spanish army as a cadet at the age of just 13. He fought in many places, firstly North Africa, where he was recognized as very competent, and became an officer in 1793. Before the French-Spanish alliance of 1796 he had fought against the French in a number of battles, and afterwards against the Portuguese.

Building within him was a love of his homeland, which he clearly considered to be South America. The British invasion of Buenos Aires in 1806 – and the way the locals hated it – taught José a lesson that he took forward into his later life – that swapping one imperial master for another was not a good thing. And so was born his zeal to help his birth country. And James Duff, later 4th Earl Fife, became instrumental in José achieving just that.

The UK did not invade South America as the Spanish had done centuries before, but instead provided assistance. One of these was smoothing the diplomatic manoeuvres for José to get from being a Spanish soldier, to getting to South America where he was to lead the fight against them, to provide effective privateer assistance in the overthrow of the Spanish in Chile and Peru. The former was managed by James Duff, now 4th Earl Fife, using his contacts throughout the British government; and the latter by Captain Thomas Cochrane, another Scotsman, who was paid to command a fleet of ships – ex British men-of-war surplus to requirements after Trafalgar – that were sold, often with their crews, to the insurgents in South America. This is quite a story, but not for now.

While James Duff was enjoying his life in Banff and London, sometimes giving rise to gossip from his antics with some ladies, José was busy liberating Argentina, then Chile and then Peru. The boundaries of those states was poorly defined back then but do loosely equate to those countries we know today. After achieving all this, José resigned his leadership in 1823 and returned to Buenos Aires, but the new political leaders there were not welcoming, perhaps being concerned for their own roles; José seemed to understand this and sailed for London. He was much feted there and the newspapers abound with dinners in his honour. Of course he met with James Duff, and took up his invitation to visit, arriving in Banff on 12th August 1824.

The story of José’s visit to Banff – and many subsequent interactions between Argentina and Banff – will be told in the town during 2024 as a consequence of the Burgh of Banff honouring him with the “Freedom of Banff”. The Bicentenary of this is on Monday 19th August 2024, with related events taking place in the town on Saturday 17th and Sunday 18th. A delegation from Argentina, and a visit from the Argentine Ambassador and others from London, will be reminiscent of a similar visit in 1950 remembering 100 years since the death of José.

++++++++++

27-Sep-23 THE ODCOMBE LEGSTRETCHER: a 17th century view of the world through the eyes of a true eccentric

(Many thanks to Sandra Cumming for this Library Story)

Have you ever had to spend hours languishing in a hot stuffy airport waiting for a flight and wondering if it is all worth it? If so, you might spare a thought for one intrepid 17th century, adventurer, Thomas Coryat (1577? – 1617). He wrote one of the earliest works by travellers that we hold in the library. A colourful character, after a good education at Winchester and Oxford and serving in the Court of James 1st, his walking feats from 1608 onwards earned him his nickname, and, never one to hide his exploits, he left a pair of his comfortable walking shoes to his Parish Church of Odcombe in Somerset!

Beginning his travels around 1608, Europe was for him but the start. He covered huge mileages, often on foot, to the Middle East and India; it was today Europe – tomorrow the Moghul Court. He may not have covered the whole of the world but even today his travels would not be for the faint-hearted.

Portrait of Thomas Coryate: NPC D2214 Engraving after an unknown artist, 1801. Copyright Creative Commons

Thomas’s work is just one of the many books on exploration, travel and geography in the Erskines’ Library allowing them to armchair travel to what was a rapidly expanding known world. Thomas seems like a character that would have been worth meeting.

His original book was titled “Coryat’s Crudities” published in 1611, and recounted his travels around some of Europe. However the copy in the Dunimarle Library (DH 570) is a reprint of that but also containing his letters from further later travels to Turkey, Palestine, Mesopotamia and India. The full title of DH 570, of three volumes, is not exactly short:

Coryat’s crudities; reprinted from the edition of 1611. To which are now added his letters from India, &c. and extracts relating to him from various authors: being a more particular account of his travels (mostly on foot) in different parts of the globe, than any hitherto published. Together with his orations, character, death etc with copper-plates.

Thomas sets out for Europe

His journeys were tough. He only just survives a scary encounter with an angry Jewish mob in Venice who object to him, perhaps somewhat unwisely, trying to convert their Rabbi to Christianity. He is rescued by the passing British Ambassador Sir Henry Wotton; he is robbed twice between Aleppo and Isfahan, yet nothing seems to dent his enthusiasm. On the way he learns Italian, Arabic, Turkish and Persian. He is an endlessly engaging character, making it difficult to encapsulate his story – so here are just a few incidents to try to give a flavour or it all.

The first two volumes of his Crudities are all about his first great journey – around Europe with Venice as his chief target. Apart from his little local difficulty with the Jewish crowd – see above – he finds much to interest him. He calls it “the most glorious peerelese and mayden citie” . He is so overwhelmed that he feels his pen is not up to it. But never fear he proceeds at pace – with something that is really rather new – a travel guide. He gives lots of useful descriptions of sumptious palaces, glorious churches, canals etc, laced with considerable history. There are useful tips about taking gondolas and warnings about the boatmen who do not get a good billing being “the most vicious and licentious varlets in the city”.

He later gives some fascinating detail on the women of Venice’s appearance – from their veils, to their hats, their dyed and dressed hair and their quite extrordinary platform shoes – called Chapineys by Thomas but seem today to be referred to as Chopines.

The Chopines lead him on to the subject of Venices’ famous courtesans, as the shoes are also worn by them. They, as he says, were “famoused over all Christendome”. The picture of his meeting with one gives some indication of their status. He knows that he is likely to be criticised for such coverage but feels that previous descriptions of the city, which omit this element, are quite simply incomplete. He then commits many pages to describing the linguistic roots of the term courtesan, the womens’ appearance, their appartments, the money they put into the economy, their cosmetics, their conversational and musical talents. We are told what happens to their children, and finally for those who don’t make enough money to fund their old age, that they “consecrate the dregs of their olde age to God” by going into a Nunnery, having before dedicated “the flower of their youth to the divell”.

A footnote: “ the knowledge of evill is not evill – only the practice of it is”. So says our Thomas as he assures us that his visit was for observation only and in the hope that he could persuade the courtesan out of her dubious lifestyle (he didn’t).

Asia and beyond

We only know about his later adventures because our Crudities is a later 18th century edition by which time much extra material relating to his adventures in Asia had been added. The way this material ever reached London is a tale in itself. At various points he pauses, writes up his notes, writes letters to friends, family and influential contacts and thrusts these into the hands of travellers on their way back to Britain. Remarkably, this postal service worked.

He did fulfil some of his ambitions, to ride an elephant and to visit the Moghul Court. He also had the opportunity to ride a camel, which he sends in a letter from the Moghul capital of Agra (about 200km southeast of Delhi – the home of the Taj Mahal) to his friends back in England in 1615. It seems the sketches he includes throughout his book and letters were of his own doing.

His concern for his legacy appears regularly. Take for instance his letter of 1615 from the Moghul Court to Sir Edward Philips, Master of the Rolls (he was a Somerset MP and thus a neighbour though Thomas is writing to him in London). In it he emphasises that however fantastic his tales sound, Sir Edward will recognise his style from knowing, what he describes as “my extravagent discourses”. He can also be assured that this really is Thomas’s letter as it will be delivered to London by one Peter Rogers , Minister to the English Merchants resident at the Moghul Court. In the letter he talks of his “insatiable greedinesse of seeing strange countries”

In a letter to a friend, also 1615 from the Moghul Court, he starts with a confession of that all too human failing of not exactly remembering when he last wrote and therefore what the friend already knows. He gives a wonderful description of his travels from the coast of the Levant, through Persia to what today is Pakistan and on to India. Just about on the border of Persia and India he meets Sir Robert and Lady Shirley on their way back from the Moghul Court to the Persian Court where Sir Robert was ambassador to the Persian emperor Shab Abbas. They are endlessly kind and gracious to Thomas but more to the point, and to his huge delight, they show him copies of his current two books which they happen to be carrying with them. They intend to show them to the Shah and interpret into Turkish key elements so that Thomas will be well received on his return journey. His fame is spreading.

Sir Thomas Roe at the Court of Ajmir, 1616, Colour photolithograph by William Rothenstein. Copyright UK Parliament, WOA 450 heritagecollections.parliament.uk

The Shirleys also show him the animals they are taking from the Moghul to the Persian court as gifts – two elephants and 8 antelopes. However it is at the Moghul court that the wildlife really impresses him for there he sees lions, elephants, leopards, bears etc but also two unicorns “the strangest beast of the world: they were brought hither out of the countrie of Bengala,which is a kingdome of most singular fertilitie”. Thomas is not the only traveller to recount “unicorns”, and he seems perfectly clear that he did see them. The scientific belief today is that unicorns never existed, so what were they? A possible suspect is the Arabian Oryx which no doubt Thomas would have seen on his travels – when seen sideways at a distance it can look like a single horn but is this really credible?

The journey ends

Finally Thomas leaves the Moghul Court intending on a long journey back home by way of Asia, the Middle East and Europe again, in all taking perhaps four years more. He details this in his last letter to his mother written in 1616. He assures her that he always travels safely by joining caravans of travellers (how many parents have heard this sort of story as their back-packing teenager sets off on foreign adventures?).

Sadly she is never to see him again for he dies of dysentry in Surat in 1617. He remained concerned about his legacy – as told in a character sketch by Edward Terry, chaplain to the British Ambassador Sir Thomas Roe, who knew him well in that last stage of his travels in India.

More aware of his mortality than he revealed to his mother, he feared being buried in obscurity; indeed the site of his grave is a matter of debate but he really need not have worried – he has been written about and celebrated and his very readable writings are still available to entertain and amaze us. Further, he is acknowledged as the first to use the word “umbrella” in an English sentence, which he picked up from the Italian practice of shading oneself from the sun; the first to use the word “ghetto” when describing part of Venice; his account of William Tell is the first time it was recounted in English; and he brought – and used – a “fork” – the everday eating implement we use today – back from Italy where it was their fashion but virtually unknown in England!

All in all, an adventurous and entertaining person.

++++++++++

13-Mar-23 ON THE TRAIL OF A PANDEMIC: 10TH CENTURY PERSIA TO GEORGIAN LONDON

(Many thanks to Sandra Cumming for this Library Story)

People you know are getting ill, some are dying, London social life has come to a virtual standstill – an epidemic is on the loose. It is becoming rampant for many reasons but greater mobility and global trade certainly contribute. This could have been 2019? But no, this was 1721 and the scourge is not Covid, it’s smallpox.

Known for millennia, smallpox was at its worst from the Middle Ages to the 19th century. In the small but interesting group of books on medical matters in the Dunimarle Library we find “A discourse on the small pox and measles, by Richard Mead, … To which is annexed, a treatise on the same diseases, by the celebrated Arabian physician Abubeker Rhazes. The whole translated … by Thomas Stack”, London, 1748.

Dr Richard Mead by Allan Ramsay. Courtesy of The Foundling Museum; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/dr-richard-mead-191947

Mead’s book is both thorough and readable. He opens with a good description of the history of smallpox before moving on to symptoms and treatments – often drawing on his own case histories and discussions with other medics. While some of the treatments used sound grim to us (a lot of blood-letting), much of the advice on diet, hydration and plenty ventilation would sit quite comfortably in a modern book – a perfectly appetising mix of cereal and dried fruits is recommended as a fibre rich food. Mead then wades into the “inoculate or not to inoculate” controversy. Again he is thorough, giving a detailed account of the history of the practice and adding a rather different prevention technique used by the Chinese. Case histories range across experiments on British prisoners in the 1720s to the use of it in very young Circassian girls destined for the slave market (sadly the earlier you inoculate, evidence suggested the less their looks were spoiled) to owners using it on enslaved workers in a sugar plantation. Mead is puzzled by why inoculation works and spends some time using his observations to speculate how it might work.

It is a fascinating book, not just for an 18th century view of knowledge of the disease but also for the translation of a very important work from Persia, from the Islamic Golden Age. It was written by Abū Bakr al-Rāzī , who lived from the end of the 9th into the 10th century and is also known by his Latin name Rhazes. In the Middle Ages his fame spread beyond the Middle East to Western Europe through translations of his work. He was and still is regarded as a key figure in the history of medicine.Rhazes was a scholar working across many fields: a physician, philosopher and alchemist who also wrote on logic, astronomy and grammar. By all accounts, he was also a humane, practising doctor. He would treat patients for free and wrote perhaps the first home medical manual by a Persian physician One Who Has No Physician to Attend Him (Kitab Man la Yahduruhu Al-Tabib) He dedicated it to the poor, the traveller and the ordinary citizen who could consult it for treatment of common ailments when a doctor was not available. In its 36 chapters, it gives advice on diets and drugs using components that could be found in an apothecary, a market place, in a well-equipped kitchen, and in military camps. Thus, every intelligent person could follow its instructions and prepare the proper recipes with good results. For example, he prescribed for a feverish headache: ” 2 parts of duhn (oily extract) of rose, to be mixed with 1 part of vinegar, in which a piece of linen cloth is dipped and compressed on the forehead”.

That Mead admired Rhazes is clear from his Preface where he details his diligent search for Latin translations of the work – especially for accurate ones. Though some certainly appeared from the 15th century onwards, Mead was determined that it was time for an English translation. What results is also a good read. We find that Rhazes is even more detailed than Mead when it comes to care and treatment of smallpox victims. Great emphasis is given not only to diet but also to medications often providing actual recipes. He makes good use of local fruits, vegetables, pulses, herbs and spices. Some remedies are very complex – just a few ingredients from one include currants, apples, quinces, and pomegranates, lentils, lettuce, coriander. One of his simplest suggests that for lessening the intensity of the disease ‘all acids are proper for this purpose, especially the water called Al-raib that is, the sour, bitter water, which swims upon buttermilk exposed to the sun”. He also devotes a chapter to remedies for the marks left by the disease – a huge issue for people. Though before it all sounds too sensible, it has to be said that in the latter section on treating scars there is mention of the excrement of various birds, lizards and mice among other more familiar ingredients.![1802 cartoon of Dr Jenner vaccinating patients, some of whom develop features of cows [Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection]](http://www.friendsofduffhouse.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/005-Gilray-300x212.jpg)

1802 cartoon of Dr Jenner vaccinating patients, some of whom develop features of cows [Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection]

This was a part of life everybody, the Duffs, the Erskines (the originators of the Dunimarle Library); they would all have known about smallpox – we see evidence across the library in both the good stories – the beginning of effective prevention through inoculation and the bad – the deaths, the disfigurements. References appear in works like Joseph Andrews by Henry Fielding and in a well-known poem by Robert Bloomfield “Glad Tidings, or, News from the Farm”, both works the Erskines knew.

![Lady Mary Wortley Montagu 1715-1720 by Sir Godfrey Kneller [Courtesy of the Yale Centre for British Art]](http://www.friendsofduffhouse.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/006-Wortley-Yale-150x150.jpg)

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu 1715-1720 by Sir Godfrey Kneller [Courtesy of the Yale Centre for British Art]

On the hopeful side they had the works of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu [1689-1762], now well-known for encouraging the introduction of inoculation after her experience of it in Constantinople. In a letter from this volume in the library, sent to a friend on April 1st 1717, she describes in detail how the old women held smallpox inoculation sessions every September using ‘a large needle’ – the one below was in use in the 18th century and is now in the Science Museum. She then goes on to say she is so convinced by the results that ‘I intend to try it on my dear little son’ and further that she intends to ‘to bring this useful invention into fashion in England’. She then gives a scathing account of her lack of faith in doctors there – she fears that they will not welcome this innovation as it will destroy a ‘considerable branch of their revenue’.

![An 18th century smallpox vaccination needle [Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, now in the Science Museum]](http://www.friendsofduffhouse.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/008-needle-Copy-Copy-300x200.jpg)

An 18th century smallpox vaccination needle [Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, now in the Science Museum]

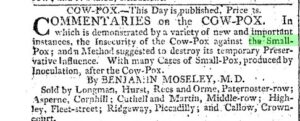

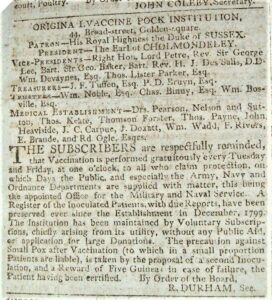

Moseley was an early and well-known opponent of vaccination – threatening all sorts of dire side-effects. However despite this, vaccination was freely available and encouraged as we see in the second advert below.

In terms of magazines, the Monthly Review, which the Erskines had taken from its very first volume, similarly covered the debate, regularly reviewing publications on both sides. Take for instance three titles reviewed in February 1807:

Cow-Pock inoculation vindicated and recommended from Matters of Fact By Rowland Hill, A.M., [1806/7?] (Hill was a zealous advocate)

Vaccination vindicated from Misrepresentation and Calumny in a Letter to his Patients, by Edward Jones, Member of the Royal College of Surgeons, 1806 (Refuting the opinions of one quaintly named Dr. Squirrel)

A reply to the Anti-vaccinists by James Moore, Member of the Royal College of Surgeons, 1806 (reviewer considers this ‘the best treatise which has appeared in the course of the controversy).

The reviews indicate that the Monthly Review took a distinctly pro-stance.

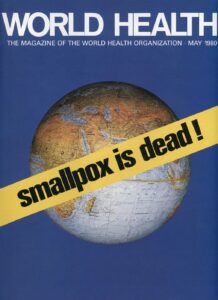

And finally what the Duffs and the Erskines of the time never knew was that over 150 years later the World Health Organisation celebrated a major success in the history of medicine – a smallpox free world.

—–

On a local note, smallpox was a disease that arose from time to time, as it did throughout Scotland and the UK. There was a small outbreak in 1732, a larger one in 1785 to 1786. The first smallpox vaccination in the UK was by Dr Jenner, given in 1796, proven a couple of months later when the child was injected with smallpox and remained completely healthy. Whether through such writings or just a natural conservatism, the local minister writing in 1798 in the Banff entry in Scotland’s First Statistical Account laments that “The practice of inoculation for the smallpox is by no means become general among the lower ranks. The too tender consciences of the superstitious interpose, to rob them of its salutary benefits …”.

Rev Mr Abercromby Gordon, the minister, reports that one in six, one in seven at the least and sometimes one in five, is the death rate from smallpox. Vaccination against smallpox became mandatory in the UK in the 1840’s.

Nevertheless smallpox outbreaks continued locally at intervals, 1848 and 1863 having been identified.

1907 Postcard showing Ladysbridge Station (now gone) in the foreground with the Hospital, often known as the Asylum, as still in place today, on the hill behind.

A major outbreak started in January 1904 in Banff, having been brought in by a couple that had just honeymooned in south Scotland, where an outbreak had started in 1901 having been brought in from a foreign ship. Reports show that the vaccination rate by this time had dropped to 63%. Banffshire did have a “Smallpox Hospital”, sited at Ladysbridge, but by February 1904 the number of beds was insufficient and a temporary building was purchased and rapidly erected near to the Ladysbridge Station. By early 1905 only three patients remained. The railway station was just south of today’s A98, today replaced by a modern house.

++++++++++

8-Jan-23 CAPTAIN GEORGE VANCOUVER

In the late eighteenth century, with trade increasing, including with the newly independent America and the Far East, the search for an easier passage for ships to the Pacific Ocean became intensified. In 1791, a three ship group sailed round the Cape of Good Hope, and ultimately to the north Pacific to search for the fabled “North West Passage”, allowing ships to go from the Atlantic to the Pacific without having to go around the feared Cape Horn at the southern end of South America. The ships were the “Discovery”, the “Chatham” and a smaller sloop, the “Daedalus”, with the mission commander being Captain George Vancouver. They sailed from Woolwich on the River Thames on 1st April 1791 – intending to take two years, but it actually took four!

Also on the voyage was Archibald Menzies. Technically he was the Surgeon on board, but as was typical he was also the appointed Botanist. This appointment was given by Joseph Banks, now the governor of Kew Gardens, but who himself had been the Surgeon cum Botanist on the Endeavour during Captain James Cook’s global circumnavigation of 1768-1771. Menzies is a key person for the link to Duff House – see below.

Also on the voyage was Archibald Menzies. Technically he was the Surgeon on board, but as was typical he was also the appointed Botanist. This appointment was given by Joseph Banks, now the governor of Kew Gardens, but who himself had been the Surgeon cum Botanist on the Endeavour during Captain James Cook’s global circumnavigation of 1768-1771. Menzies is a key person for the link to Duff House – see below.

Captain Vancouver wrote journals of the adventures; some of these were printed in 1798 but it was another three years, 1801, until all the volumes were printed and available.

Captain Vancouver wrote journals of the adventures; some of these were printed in 1798 but it was another three years, 1801, until all the volumes were printed and available.

The main purpose of the voyage was not achieved, ie no northwest passage, but nonetheless the voyage was considered a success as much of Australia, New Zealand and the west coast of North America were charted in vastly more detail than had previously been done; plus Captain Vancouver achieved some very good diplomatic outcomes increasing British influence in the area. As was the plan, the Discovery and Chatham were to sail home by going south along the west coast of South America and round Cape Horn. There were instructions not to call at any South American ports to avoid any diplomatic issues with the Spaniards were who largely considered to control South America.

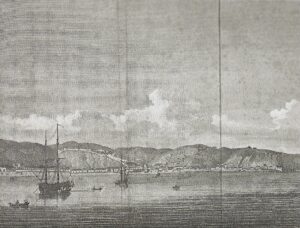

Unfortunately, during the voyage, the main mast, main spar and most of the rigging of the Discovery were found to be rotten and unfit for the perilous trip around Cape Horn and it’s frequent storms. They had no choice but to find replacements and they sailed into the port of Valparaiso in what today is Chile (which only became Chile in 1820 thanks to Jose de San Martin – also with a strong connection to Duff House!). At the time Chile was in the Viceroyalty of Peru; under Spanish control.

Captain Vancouver makes fairly detailed descriptions of every place they visited – after all this whole trip was a real Star Trek adventure – literally termed a Voyage of Discovery. Valparaiso mainly had single storey buildings; no higher because of frequent earthquakes; and mostly built of mud, so they could easily be rebuilt!

Their reception was in fact very friendly and helpful, as good reports about Captain Vancouver had filtered down from North America, and the necessary repairs received much cooperation. In fact, the officers even received an invitation from the Captain General and Viceroy of Chile, Don Ambrosio O’Higgins de Vallenar, to visit him in Santiago. This could hardly be refused, and a rather uncomfortable three day journey on mule back followed! Some of the descriptions of the places they passed through are in fact very complimentary – much of the food provided by the “peasantry” was described as being good, despite the accommodations being like hovels!

They finally arrived at Santiago and were much feted, with crowds of people and banquets given in their honour. They were greeted with much cordiality by His Excellency who surprised them all by being fluent in English – later finding out he was originally born in Ireland and hence the O’Higgins name! Of the Governor’s reception very little detail is given of the many courses served – an omission which in later years has led to much speculation! In fact Captain Vancouver is much more taken with the very finely dressed ladies that approached them after the meal and invited the officers to join them at a little distance from the palace; it is easy to read some disappointment in Captain Vancouver’s diary that he “thought it would be more respectful to pay our compliments to his Excellency in the audience-room”.

Not so however a few evenings later in the visit, when they dined with a Senor Cotappas, “a Spanish merchant of considerable eminence”. After some entertainment of music and dancing (which the British couldn’t partake in, much to their “mortification”, as the steps were too complicated) and most people had retired, some of the ladies sent a message, requesting that the officers join their party on the cushions arranged at the other end of the room; “with this we instantly complied”! He goes on to say “the generality of the ladies are not wanting in personal charms”. One of his descriptions is then of the ladies underwear, so the reader can draw what conclusions they like! There are in fact two pages of his diary attributed to the ladies to whom he was “indebted for the most civil and obliging attention that can be imagined”.

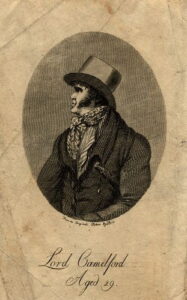

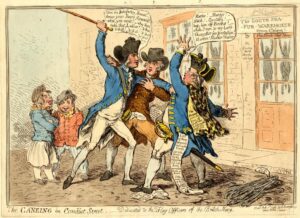

The officers returned to Valparaiso after a couple of weeks, the repairs on the ships completed, and the voyage continued safely around Cape Horn – although they experienced the expected storms. On the last part of the voyage it seems some nefarious goings-on were in play. A third well-known person on board from the start of the voyage was one of the midshipmen, the Honourable Thomas Pitt; he was not a well-behaved young gentleman and Captain Vancouver frequently disciplined him, including having him flogged on a number of occasions. In exasperation he had dismissed Pitt in October 1794 and sent him home on the Daedelus.

Unfortunately for Captain Vancouver (left), Thomas Pitt (right) was the cousin of the then Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger. The nearer Captain Vancouver got to London, the more concerned he became that his treatment of Thomas Pitt may be seen as really harsh and give him difficulties once he landed. Not only that, but on his return home, Thomas had become the 2nd Baron Camelford on the death of his father; this placed him socially ranked higher than Captain Vancouver. As it was common practice of ships officers to keep their own journals it seems the Captain must have appropriated all of them before the ship docked in London, to avoid there being evidence against him should he face charges for his harsh treatment. We know this not only because it was common practice, but because Menzies had told Banks in various letters to him that he was keeping a journal; yet the only journal to survive from this ground breaking round the world voyage of discovery, is that of Captain Vancouver himself.

Unfortunately for Captain Vancouver (left), Thomas Pitt (right) was the cousin of the then Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger. The nearer Captain Vancouver got to London, the more concerned he became that his treatment of Thomas Pitt may be seen as really harsh and give him difficulties once he landed. Not only that, but on his return home, Thomas had become the 2nd Baron Camelford on the death of his father; this placed him socially ranked higher than Captain Vancouver. As it was common practice of ships officers to keep their own journals it seems the Captain must have appropriated all of them before the ship docked in London, to avoid there being evidence against him should he face charges for his harsh treatment. We know this not only because it was common practice, but because Menzies had told Banks in various letters to him that he was keeping a journal; yet the only journal to survive from this ground breaking round the world voyage of discovery, is that of Captain Vancouver himself.

The lack of Menzies’ journals surviving is a real pity because clearly he recorded much of his botanical discoveries and observations. However, Menzies did bring back with him as many samples of seeds, drawings and in some cases, plants, as he could manage.

For the last part of the voyage Vancouver even had Menzies confined to his cabin and Menzies’ personal servant was effectively press-ganged into the crew. This nearly had some dire consequences as the various plants being propogated by Menzies were not looked after for a few weeks.

Vancouver took himself off the ship passing Portsmouth so his report could be submitted before anyone else’s, to try and avert a court martial, while the Discovery carried on to the Thames. All of Vancouver’s efforts however didn’t work and his reputation thoroughly suffered; his worst moment was arguably when Thomas Pitt, now Lord Camelford, crossed paths with George Vancouver – on Conduit Street in London. The well-known magazine, Punch, printed a cartoon of the “Caneing” in 1796.

Vancouver took himself off the ship passing Portsmouth so his report could be submitted before anyone else’s, to try and avert a court martial, while the Discovery carried on to the Thames. All of Vancouver’s efforts however didn’t work and his reputation thoroughly suffered; his worst moment was arguably when Thomas Pitt, now Lord Camelford, crossed paths with George Vancouver – on Conduit Street in London. The well-known magazine, Punch, printed a cartoon of the “Caneing” in 1796.

Captain Vancouver is today remembered by giving his name to the city of Vancouver and related places in British Columbia, and also Mount Vancouver in New Zealand. A number of other places were named after his officers (eg Puget Sound) and his friends (eg Mount St Helens).

Thomas Pitt became known as the Gentleman Thug, getting away with some very violent crimes including a murder; but he challenged one too many people to a duel, and was killed at the age of just 29.

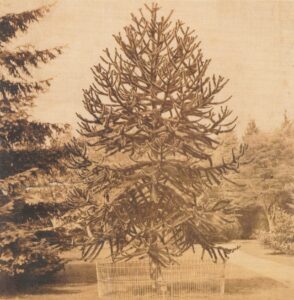

Back to Archibald Menzies and the link to Duff House. One of the items he collected from his four weeks ashore in Valparaiso, Chile, was some seed from the Auracaria Araucana – the Monkey Puzzle. If today you walk in Duff House woods, to the west of the Ice House, you may come across a seed head that looks like this picture – just about two inches long.

Back to Archibald Menzies and the link to Duff House. One of the items he collected from his four weeks ashore in Valparaiso, Chile, was some seed from the Auracaria Araucana – the Monkey Puzzle. If today you walk in Duff House woods, to the west of the Ice House, you may come across a seed head that looks like this picture – just about two inches long.

This is a male seed head; trees of the Monkey Puzzle are either male or female. The other well known Monkey Puzzle tree in the area is the one at Banff Castle; this is a female tree which has considerably larger cones. Unfortunately these two Monkey Puzzles seem to be too far apart for one to fertilise the other.

Although Archibald Menzies didn’t bring a female Monkey Puzzle cone back from Chile, he certainly did get his hands on some viable seed. A later Director of Kew Gardens, Joseph Hooker, started a story that while in Santiago, Monkey Puzzle seeds had been served as one of the courses at the Viceroy’s dinner – indeed they are edible – and that Menzies had pocketed a few. This story was repeated a number of times in various publications and became the commonly known background to how the Monkey Puzzle tree came to the UK.

There are however a few issues with this story: Monkey Puzzles do not grow in the vicinity of Santiago nor near Valparaiso; also, to be edible, the seeds have to be cooked – and cooked seeds aren’t viable for growing. Instead it seems likely that as a collecting botanist Menzies had seen the seed – perhaps at that dinner – and arranged with the locals for the seeds to be sent to him. A fertilised female cone is very fragile and difficult to transport so perhaps he only received a few seeds.

Menzies obviously planted some seeds and six survived the journey back to the UK. It is believed that the distribution of all six of these Monkey Puzzle seedlings is now known; unfortunately none have survived to the current time. For a time there was a vague hope that the very large tree in Duff House woods just might be an early Monkey Puzzle, if not from Menzies (possibly as a gift from King George 3rd who had access to the seedlings and was a friend of the 4th Earl Fife), then from the next explorer James Macrae, who did bring viable seeds back; or even a tree brought over by José de San Martin when he visited in 1824.

However not only is the Duff House tree just not big enough to be as old as a Menzies, Macrae or San Martin tree, it is now known that the Duff House tree was not planted in its present position until about 1850 – even though it was probably several years old at that point. The year 1850 may well be very relevant – as James, the 4th Earl may have planted the Duff House Monkey Puzzle in memory of his friend José who died that year.

However not only is the Duff House tree just not big enough to be as old as a Menzies, Macrae or San Martin tree, it is now known that the Duff House tree was not planted in its present position until about 1850 – even though it was probably several years old at that point. The year 1850 may well be very relevant – as James, the 4th Earl may have planted the Duff House Monkey Puzzle in memory of his friend José who died that year.

This photo is the only known photo of a Menzies Monkey Puzzle – brought back as a seedling on the voyage described in the DH Library Book DH 1045. This was taken at the Dropmore Estate (Buckinghamshire) sometime before 1872.

Thanks go to David Gedye for much of the background to the Monkey Puzzle information in this Library Story.

++++++++++

11-Mar-22 OAK GALLS, MEDIEVAL SCRIBES, ISAAC NEWTON and JANE AUSTEN

The recent ‘Library Story’ Sturgeon and Sturgeon from the 14th century centred around an early printed work “The Lawes and Acts of Parliament, maid be King James the first” [DH LIB 1719]. There are a number of other legal books in the Dunimarle Library, and another of the most interesting is a manuscript, ie handwritten, ref DH LIB 2154. It is a slightly battered volume that might be described as a legal common place book as its owner has copied various legal texts into his own notebook.

The link between the two above books is in the various provenances – or owners’ names – inscribed in the works. In this case the name is “Halkerstone”, the printed book belonging to “Joannes Halkerstone” in 1731, and the manuscript initially belonging to “Guliolmi Halkerstone” in 1703, but John Halkerstone is also mentioned.

A number of books from the Halkerstones have found their way into the Dunimarle Library, seemingly via a family they were related to by marriage, the Kers.

There is reasonably good evidence that this group of books was donated to Magdalene Sharpe-Erskine, the last surviving member of the Erskine family who created the Dunimarle library, by a neighbour, one Captain Ker, in his will of 1848. The will was subject to a very tortuous court case in which Magdalene was the defender as the will was contested by Ker’s family. Ker, through a series of codicils, and ‘death-bed revocations’ basically created an unholy mess. We know all this as the case, held in 1851, was printed in a volume of Scottish legal cases.

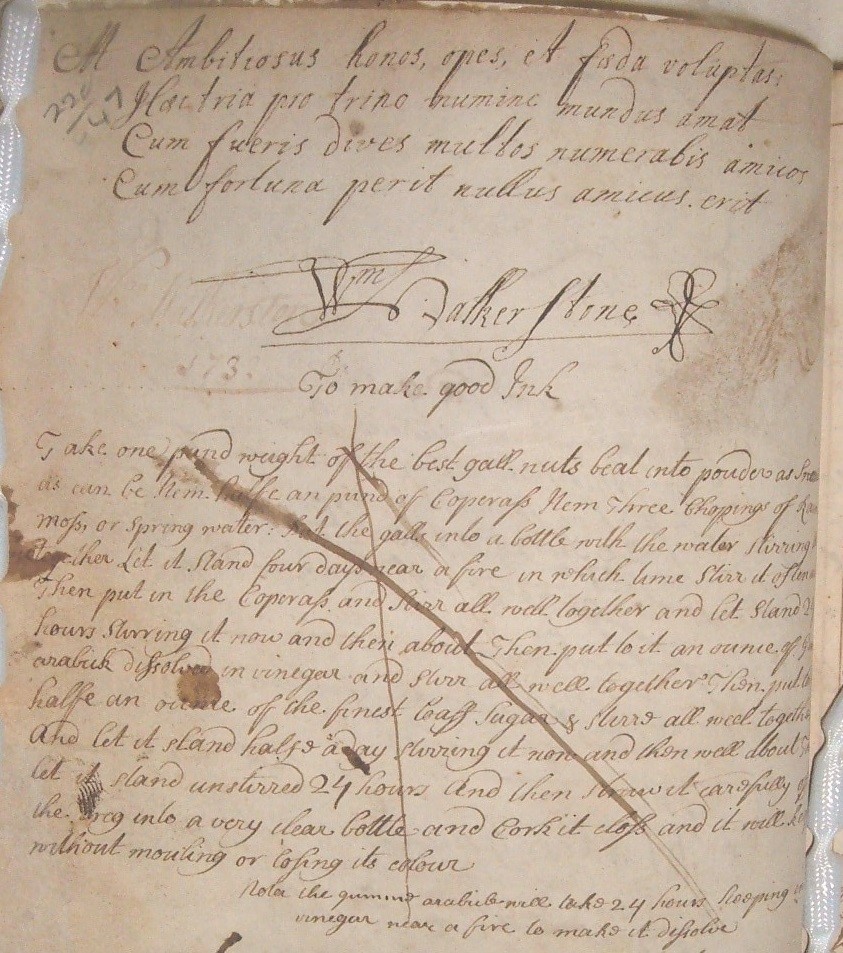

Eighteenth century handwriting is not always the easiest to read, so this Library Story looks at just one page from the manuscript book! And it is this page that leads to the link between the above four pictures: oak galls, a medieval scribe, Isaac Newton and Jane Austen.

What links this happy band is that they all used the same ink recipe – an essential precursor to written work into the 19th century. Perhaps that is why the first page of this Dunimarle Library manuscript is that ink recipe:

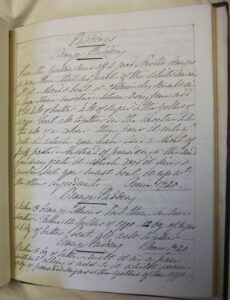

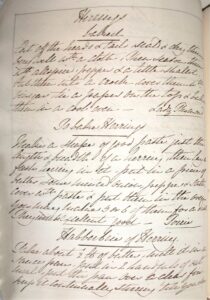

To make good Ink

Take one pound weight of the best gall nuts beat into powder as small

as can be Item: halfe an pund of Coperass Item: three Chopings of …

moss or Spring water: Put the galls into a bottle with the water Stirring it

together. Let it Stand four days near a fire in which time Stir it often

Then put in the Coperass and stirr all well together and let it Stand 24

hours Stirring it now and then about. Then put to it an ounce of Gumm.

arabick dissolved in vinegar and stirr all well together. Then put to

halfe an ounce of the finest loaff Sugar & stirr all weel together

And let it stand half a day stirring it now and then well about …

let it stand unstirred 24 hours and then strain it carefully of

the dreg into a very clear bottle and Cork it closs and it will keep

without mouling or losing its colour.

Note the gumm.. arabick will take 24 hours steeping in

vinegar near a fire to make it dissolve.

Today the ingredients might not be immediately familiar but each provided a key element of the ink.

“gall nuts” are oak galls or oak marbles (sometimes referred to as oak apples, but these are generally less spherical and larger, and no good for ink making!), naturally arise on oak trees, a reaction to chemicals injected into the twig by a small wasp. They are typically half to one inch (2.5cm) in diameter. The gall is used by the wasp larvae to protect it and feed it. They are key for ink as they rich in tannic acid;

“Coperass” is ferrous sulphate (ie iron sulphate, not copper as the word suggests!).  Also known as green vitriol;

Also known as green vitriol;

“Gumm Arabick” came from the dried up sap of two types of Acacia trees found mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and Arabia, that is water soluble. The Levant was also said to be the source of the best oak galls. Gum Arabic is perhaps the most interesting of this list for its sheer versatility and long history. Used in the textile industries of the 17th and 18th century, it is still in use today in a range of industries from pharmaceuticals, food, paints and printing to photography. It was once an important and controlled export from various European powers’ colonies and is still an important export for Sudan. It provides control of the surface tension of the ultimate ink making it flow off the nib better, as well as stabilising the colour over time.

paints and printing to photography. It was once an important and controlled export from various European powers’ colonies and is still an important export for Sudan. It provides control of the surface tension of the ultimate ink making it flow off the nib better, as well as stabilising the colour over time.

Loaf sugar and vinegar would have been readily to hand.

Most of the measures are quite familiar but the “chopin” may not be – an old Scottish measure equal to about a quart (ie two imperial pints or just under one litre). Interestingly a “chopin” equalled two of the delightfully named “mutchkins” – another old Scottish liquid unit of capacity.

When it came to preparation of the ingredients, a helpful note by a physician in 1619 tells us that the process of getting the tannic acid from the galls can be speeded up by boiling the galls for as long as it takes to repeat the Pater Noster three times!

In Martha Lloyd’s ‘Household Book’ (Martha was Jane Austen’s closest friend after her sister Cassandra), we can also find the recipe for ink that Jane used. In Isaac Newton’s laboratory notebook, we find his recipe. They are almost identical recipe to Halkerstone’s – centuries apart – the only difference is that they both have ale in their mix rather than water and vinegar.

One slight puzzle is why were Isaac Newton and Jane Austen making their own ink? By the 18th century stationers in Britain sold paper, quill pens and ink. Three centuries earlier, scribes copying manuscripts in that hive of intellectual activity, Florence, could buy ink. It seems some writers not only made their own ink, they also cut their own pens. Were they just better quality?

Next time we write a letter or note (a rarer activity these days) we might reflect on how much more complicated it was in days gone by.

++++++++++

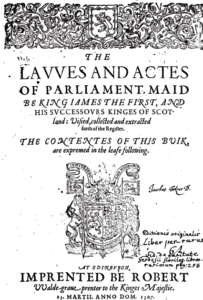

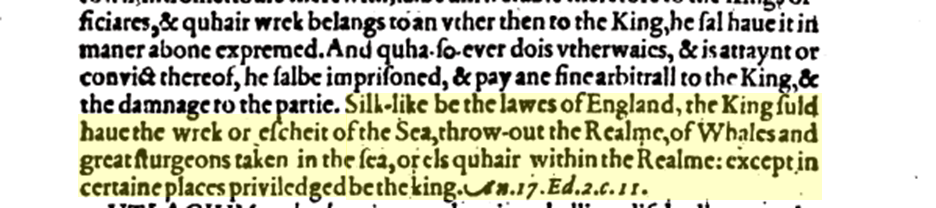

18-Dec-21 STURGEON AND STURGEON FROM THE 14TH CENTURY

This title is reflective of both the fish and the First Minister – there is a legal connection! And with a link to the Library in Duff House – the earliest book in the Library in the English language (albeit not modern English!), rather than in Latin is “The Lawes and Acts of Parliament, maid be King James the first” [DH LIB 1719].

King James the First of Scotland was born 1394, and became King of the Scots at the young age of just 12. Scotland was of course a completely separate country to England until the Act of Union in 1707. But by then James was being held as a prisoner in London. Although nominally King from 1406 when his father Stephen died, he was held prisoner in London until 1424. Scotland was not a settled and unified country at the time, but once back in Scotland James 1 did much to regulate the laws and became a very popular leader with the general people, if not the Lairds!

He produced many laws and history reports he was generally found to be very fair. These laws were published for wider view in 1597 by John Skene; his family’s land was at Bandodle (southwest of Inverurie) in Aberdeenshire. He later settled south of Edinburgh after a much travelled career in the legal profession. The copy in Duff House is one of these first editions.

The book is over 900 pages – representative of the many laws of James 1st. Nearly everyone of these has been repealed or changed over the years, but there is at least one that is still valid today – and that is where the Sturgeons are relevant!

The fish, the Sturgeon, is not a well known fish nowadays around Scotland, but clearly in the fifteenth century it was more common. But the law as written by James 1st also applied to whales, and whales are certainly no uncommon around our waters. What James actually did was repeat a law of King Edward 1st (of England 1272 to 1307), but who tried to claim sovereignty over Scotland resulting in opposition by William Wallace, leading to the reign of Robert the Bruce in Scotland – as referred to in the Duff House Mausoleum.

Putting into more modern English, the 14th century law reads:

“The King should have the wreck or gift of the Sea, throw-out the realm, of whales and great sturgeons taken in the sea, or elsewhere within the Realm.”

In the centuries since there have been some modifications, defining the whales as those that could not be pulled by six oxen. In July 1999 as part of the Scottish devolution, this was again defined as whales of 25 feet (7.6m) or more belong to the Crown. The Scottish Government currently led by Nicola Sturgeon, on behalf of the Crown, has first claim on such Royal Fish of sturgeon and large whales. The last Royal Whale locally is believed to have been the Minke Whale on Boyndie Beach in 2014.

Today it is a requirement that all whale strandings in Scotland when found should be reported immediately. If dead, a whale, any cetacean, should be reported to SMASS (07979 245893); and if live to the BMDLR (01825 765546) or SSPCA (03000 999999), who will try to provide rescue for the animal.

++++++++++

8-Oct-21 A FRIGATE TO CALCUTTA

DH1288 is a small book and it has no pictures; nevertheless it is one of those books that is actually quite gripping. The title belies what is inside: “Prospectus of A Plan for the Building and Equipment of a Frigate” to sail between London and Calcutta.

Most people may associate the word “frigate” with a warship, but in reality is just means a fast ship of a certain size. In this case this Prospectus is aimed at carrying only passengers, by trying to cash in on the growing trade with India.

The book is dated 1824, a time when trade with India and the Orient is starting to show signs it could blossom. In 1824 a total of ten ships sailed from the UK to various Indian ports; each of these would take about five or six months to get there – the only route being round the bottom of South Africa; and the passengers probably had a few more weeks after that to reach their destination. This was not an easy journey, and the duration clearly was acting as a brake on rapid expansion.

To set the scene, but of course unknown to the author of this Prospectus, a number of technological developments would happen over the next three decades or so, allowing the trade with India and the East to balloon from the 1850’s onwards:

• starting in 1834, mail and passengers could instead travel through the Mediterranean, 84 miles across the desert to the Red Sea, and then by ship to India;

• the first oceangoing steamship – a paddle steamer – went into service in 1838; although long voyages were difficult due to the limitation of the amount of coal that could be carried, plus piracy in the area. So in 1839 Aden, at the southern end of the Red Sea, was established as a supply and defence port;

• the first propeller driven commercial vessel – widely attributed to the Scotsman James Watt – was in 1847;

• but the big innovation was the Suez Canal, opened in 1859 after building for 10 years.

So the Prospectus, dated 1824, not being away of what was going to happen, was proposing to build a fast ship, imitating the best of the then Royal Navy ships, but built solely for passengers, to sail around the Cape of Good Hope and save time on the passage. The book describes, in words, the features the frigate would have. These included being built in one of the foremost shipyards on the Thames. She was designed with 60 passenger cabins, with a ship of 1200 “tons” (in shipping parlance this is actually a measure of volume, not weight) that would have been about 46m long, and 12m wide – tiny compared to today’s standards of course. The total crew was going to be about 200, plus up to about 200 passengers; although this did not include the twelve envisaged musicians that would provide some of the entertainment on the voyage! Other attractions included a top chef, baths, fencing lessons, recliner chairs – in fact as many comforts as the author could envisage to attract passengers.

One of the comforts the author seems proud of, is that the ship will be fitted with fixed iron tanks to be filled with fresh water to last the duration of the voyage (rather than the more traditional wooden barrels for water). The tanks could be filled from the deck (hence avoiding a lot of handling barrels), thus minimising the time needed to fill with water. From these tanks a piping system and pumps are to be fitted; what sounds old to us, but was the latest technology at the time, was that the piping system would be made of lead; as indeed many later Victorian water systems were!

The design of the ship was intended to be very advanced for it’s time based on the verbal description. The fastest and safest Royal Navy vessel at the time was HMS Unicorn – whose restored hull can now be visited in Dundee. To be correct, it wasn’t the Unicorn that was the fastest, because she has never sailed under her own power, never having had masts, but her close sister ship HMS Trincomalee (now fully restored in Hartlepool). So it is envisaged that the ship described in this Prospectus would closely resemble these fast frigates, minus of course the guns and gun ports and other military fittings! This image is by a modern copyist.

There are just two known copies of this Prospectus; the one now in Duff House, and one in the Illinois Centre for Research Studies. The original print version leaves various blanks, mostly as to what the income and expenditure are expected, and hence the profit that investors could envisage. For whatever reason the Duff House copy has several of those blanks filled in with handwriting; the Illinois copy is blank. With a total build cost of £32,000, 64 shareholders were sought. The annual expected return per share of £500 was forecast as a minimum of £156 after voyage costs; a return of over 30% obviously meant to sound attractive!

For interest, the best cabins were envisaged would be charged at £600 (per cabin) for a trip, the not so good ones at £200; both all inclusive fares. With two trips a year that equates to £48,000 income.

No record however can be found of what might be considered such an attractive business proposition actually taking place. Perhaps investors realised that sailing ships were being superceded, perhaps the Suez Canal plans, that started in 1799 with Napoleon Bonaparte, had recently hit the news (NB it took so long – 50 years – to negotiate a Concession with Egypt as poor calculations initially showed the Red Sea was 30 foot higher than the Meditarranean!)

Neither do we know who the author of this Prospectus is. Clearly he was a man of means as he was willing to immediately advance a sum towards the project – unfortunately that is one of the blank spaces in both copies! It might just have been John Drummond Erskine – one of the Dunimarle family. He had worked for the East India Company until 1812 and clearly retained a continued interest in all things Indian. Perhaps he thought he could see an opening in the market, perhaps he was just asked to be an investor, there is no indication.

For a sailing ship idea, in hindsight, it was probably a few years too late!

++++++++++

17-Aug-21 PARIS – WE’RE HERE (Paris part 2)

Back in 1815/16 obviously many visitor attractions that people go to Paris for today did not exist. But many did and are described in Planta. A selection includes:

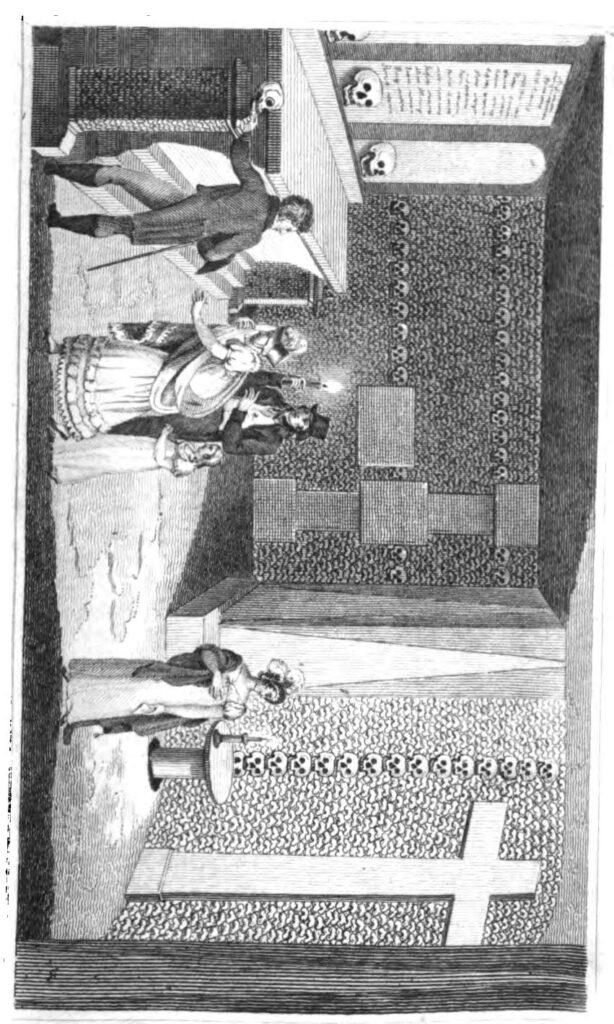

The Catacombs were a relatively new addition to the tourist experience in Magdalene’s day. It was only in 1809 that they were opened to the public by appointment. A register was placed at the end of the circuit, where visitors could write their impressions. It was filled very rapidly because these visits had

quickly become a success with both the French and foreigners. Today’s guidebook fairly briefly describes it as a “a 2km walk through the creepy ossuary and definitely not for the faint-hearted” while Planta gives them considerable space. He seems to swing from the quite callous description of bones as a feature of interior decoration “This avenue conducts to several apartments resembling chapels, the walls of which are lined with bones, variously and often tastefullyarranged … and others [altars] are ingeniously ornamented with skulls of different sizes” – yet with reference to an inscription further on relating the 87 cubic metres of bones removed from one cemetery to the Catacombs, he comments “That man must have been utterly destitute of taste, and feeling, who suggested the record of this disgusting admeasurement of the perishing remains of the human frame”.

Notre Dame Cathedral. The oldest religious edifice in Paris and the mother church of France. The picture in Planta is not all that inspiring,

but is quite surprising, almost as though the artist had not see the real thing. There is no sign of the huge rose window, the rest of the cathedral behind this west front appears to be no more than a single storey – yet the drawings of Napoleon’s “coronation” in 1804 clearly show the bulk of the building as the core is today, before and after the 2019 fire; and no sign of the famous flying buttresses down the sides.

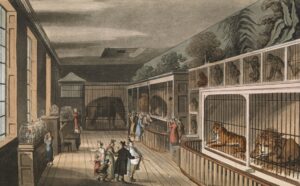

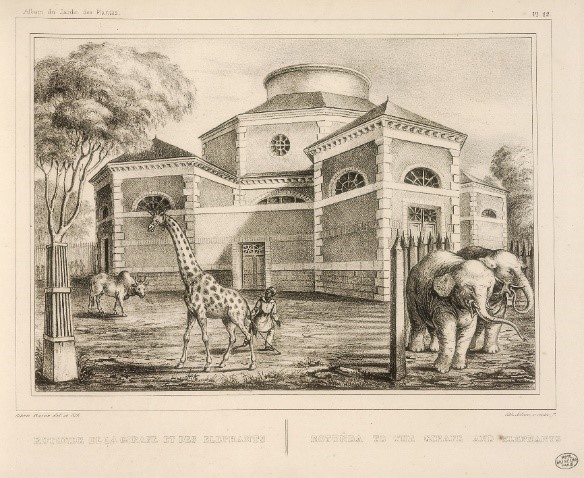

The Menagerie was another new experience for the Paris visitor of 1815, although it was formally called “Jardin Royal des Plantes” because of it’s botanic garden. There were – and are – numerous halls showing exhibits from every branch of natural history – each affording “inexhaustible amusement and information”.

From 1798 onwards some large animals arrived – elephants, lions, tigers, panthers, hyenas, wolves, camels, ostriches, bears, buffaloes (animals requisitioned by the armies of the National Convention, then by Napoleon, gifts from monarchs and animals brought back from expeditions, among others).

[Wolf and Menagerie pictures are not from Planta but other contemporary books]

The Paris aviary “contains a collection of every bird known in France and the neighbouring kingdoms, arranged according to their species and habits”.

The equivalent in London at the time was the menagerie at the Tower of London which had a very similar list of animals [picture not from Planta].

Unfortunately in 1870 during the siege of Paris by Prussian forces, many animals were killed by the bombardments, and others were slaughtered to feed the population.

1812 saw the inauguration of the rotunda, built in the shape of the Légion d’Honneur cross, which had been established in 1802 by Napoleon. This picture also shows elephants and giraffes [taken from Album du Jardin des Plantes de Paris, 1838]

Today the emphasis is on smaller animals and the protection of endangered species such as red panda and the binturong or bearcat – but this is not what what Magdalene would have seen.

Planta promises much about the Paris menagerie. There would have been plenty to “amuse or terrify the spectators by their howling” Lions, tigers, panthers, hyenas – and even kangaroos. Some aspects seem quite enlightened for example “where it could be accomplished, the trees and shrubs of the animals’ native climes, or the vegetables in which they most delight flourish within their enclosures” – being a camel was less fun “Two camels are perfectly domesticated, and more than earn their subsistence by turning the wheel of the machine which supplies the gardens with water”. And for a rest from all the excitement, he commends “… at the foot of the hill are several little casernes, at which he [the tourist] may be supplied with fruit, eggs, milk, coffee and tea” which does not sound so much worse than the modern equivalent “ …. fast food stands offer a range of snacks to take away (sandwiches, crêpes, drinks, etc.) or eat in” [Menagerie’s current website]

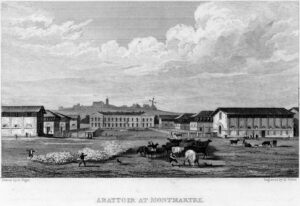

Slaughterhouses may not be on the ‘must see’ list today but bizarrely they really were in Magdalene’s time. This was not a one-off quirk of Planta’s as they feature in Magdalene’s other contemporary guidebook of Paris by Galignani – [Paris Guide 1821 DH848]. Montmartre’s was considered a fine example.

Here is Planta “On entering it [the slaughterhouse of Montmartre] , the stranger perceives no disagreeable smell; he witnesses no disgusting sight; and often he would not suspect the purpose to which the building is devoted. The English traveller should not fail to visit these useful edifices. He will return with a wish to reform those nuisances, and abodes of cruelty, filth, and pestilence, which disgust him in the capital of his own country” [p.314] Galignani is similarly enthusiastic about the new abattoirs of Paris and at even longer length and stronger language compares London’s facilities very unfavourably with them “These magnificent establishments, which were open for the public service in October 1818, amply deserve the intelligent traveller’s notice” [p.219]

Versailles – the ‘must see’ parts of Versailles have changed little except that Planta’s description are more detailed especially of the main Salons but he does warn that the 1815 tourist will miss some of the former glories as not only have certain works of art gone to the national museum (Louvre) others have been returned ‘to those to whom they rightfully belonged’ [p.486]. However he does reassure that there are still some of ‘the best works of the French school’ on view.

Eating out – this is a modern guidebook must and Planta was no different in 1814. He has many positive suggestions but also a grim warning [p. 113] “Some restaurateurs profess to furnish four dishes, half-a-bottle of wine, a dessert, and as much bread as the guest chooses to eat, for 30 sous (1s 3d) They likewise add, as an inducement to the Parisian, that their saloons are gilded and decorated with mirrors – I would not, however advise the Englishman to venture into those abodes of splendid filthiness. The almost ochre-coloured table-cloth; the rusty fork; the prongs of which are half filled up with dirt; the greasy plate, the yet greasier waiter, and a complication of villainous odours, will render it impossible to him to eat one morsel …. He may be assured that there is nothing in the vilest eating-house, in the worst part of London, half so filthy as the cheap restaurateurs or traiteurs in Paris.” London’s abattoirs may have been found wanting but Planta is prepared to be even-handed about London/Paris comparisons!

And Planta does not rate frog’s legs either – totally overpriced! The traveller “would no doubt be astonished to find that a small plate, at a first rate hotel, would cost him a guinea” (about £800 today!).

A tail piece

One final intriguing element of Magdalene’s Planta is the little fabric samples pinned into the inside back cover with annotationsof prices and ideas on use -– the first being labelled ‘Long Gloves’ [left above]. Planta does not give huge coverage to the business of shopping but he does note the price of Wellington boots ie 16 francs [p115] and indicates that while men’s clothing is reasonably priced, women’s ‘may be considered dear’ – clearly this does not put Magdalene off. Wellington boots (as portrayed here by the man himself in a portrait by James Lonsdale, 1815) were only a very recent name in the footwear world – perhaps of more interest to Magdalene’s army general brother James!

++++++++++

3-Jul-21 PARIS HERE WE COME (Paris part 1)

While we all wait for the lights to change from red to amber to green in this time of a pandemic so that travel can be opened up, there are clear reflections on a similar time in the past about the opening up of travel opportunities.

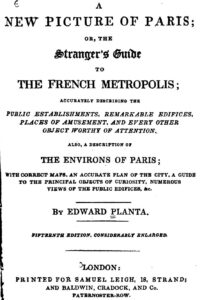

Even as Napoleon escaped from Elba and fought his final battle at Waterloo in June 1815, the writers of guidebooks were ahead of the game. The dust had hardly settled after the Napoleonic Wars before a flood of English language guidebook writers descended on the cities of Europe. These new guidebooks aimed at a broader market than the grand tourists of the previous century and in the travel section of the Dunimarle Library there are the very latest travel guides for Paris, Geneva, Florence, Siena, Rome and Naples, all published within a short period just after the year of Waterloo. Of particular interest, and published with the expectation of peace, is Edward Planta’s A new picture of Paris; or, The stranger’s guide to the French metropolis; … to which is added, a description of the environs of Paris, with correct maps and an accurate plan of the city, 1814. [DH LIB 1234]

Even as Napoleon escaped from Elba and fought his final battle at Waterloo in June 1815, the writers of guidebooks were ahead of the game. The dust had hardly settled after the Napoleonic Wars before a flood of English language guidebook writers descended on the cities of Europe. These new guidebooks aimed at a broader market than the grand tourists of the previous century and in the travel section of the Dunimarle Library there are the very latest travel guides for Paris, Geneva, Florence, Siena, Rome and Naples, all published within a short period just after the year of Waterloo. Of particular interest, and published with the expectation of peace, is Edward Planta’s A new picture of Paris; or, The stranger’s guide to the French metropolis; … to which is added, a description of the environs of Paris, with correct maps and an accurate plan of the city, 1814. [DH LIB 1234]

The youngest of the Erskines, the family who created the Dunimarle Library, Magdalene, (1787-1872), had been prevented travelling in her early years by revolution in France and then war. With her father and two brothers all senior army officers and on campaign in Europe and America, and a third brother in India, she would have been very much aware of a wider world than that of her home in Fife. No doubt this awareness was heightened by her brother James, who had married into the Paget tribe – whose published letters are awash with reports and comments on events on the Continent. We can imagine that by 1815 Magdalene would have been desperately keen to explore – and all the evidence is that she did just that. Planta in hand, she was off to Paris.

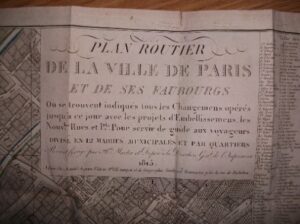

Magdalene was clearly taking it seriously. We find in the Library along with those latest guidebooks, a wonderful fold out map of Paris [DH LIB 2143]

a wonderful fold out map of Paris [DH LIB 2143]

a trusty French-English pocket dictionary and a quite formidable grammar – “When son, sa, ses, les, leurs, are preceded by a substantive of inanimate things, they cannot be joined to a second substantive in the nominate or accusative; but when that second substantive is in the same part of the sentence, and relates to the same verb as the first ….” [ from Magdalene’s copy of Alexandre Scot’s Rudiments and practical exercises for learning the French language … 1815; DH LIB 285].

first ….” [ from Magdalene’s copy of Alexandre Scot’s Rudiments and practical exercises for learning the French language … 1815; DH LIB 285].

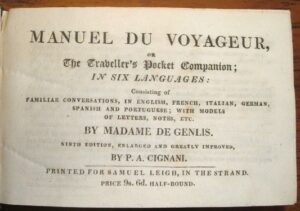

Somewhat more familiar to today’s tourist’s would have been her multi-lingual phrasebook, Manuel du Voyageur [DH LIB 335], its topics bringing alive some of the trials of contemporary travel e.g. Conversations on the Post Coach – “No , I do not object to the smell of tobacco” (though maybe tobacco was not the worse you faced?) and at the Inn Might I have a tub for bathing or at least a bucket? Warm my bed and put a little coarse sugar into the warming-pan;* I have my own sheets; but I always have sheets from the inn, in order to spread them over the mattress, afterwards I spread my own over them”.

But back to the guidebook.

This little Planta guide may not look the most exciting book as it sits on the shelves of Duff House, but it repays a closer look. We know Magdalene is in Paris because of a note “Magdalene Erskine Paris Feb. 16 1816”.

A further couple of pieces of evidence add to the picture. An insignificant bit of paper, part of a small group of Erskine family letters and personal papers which have survived with the library, turns out to be an invitation to dinner, dated 16/ 1/1817, to Miss Erskine, from Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord (1754-1838) seen here in a portrait by Prud’hon dated 1817:

The invitation is just a small single sheet folded; one side having the invitation, seal and address; the other Magdalene’s acceptance. Talleyrand was a name to be reckoned with – a major player in the European diplomatic manoeuvrings of the period. It is not surprising that Magdalene was keeping such company – she had all sorts of connections in that world through her own family and those Paget in-laws.

And speaking of the Pagets brings us to another little snippet of gossip which placed Magdalene in Paris around the period. The Divorce. This involved her brother James, his wife Louisa Paget and Sir George Murray, with whom Louisa was having an affair by 1815, and whom she eventually married. When James sues Sir George, in 1824, the graphic details of the goings on in Paris, where they all were, are spread across a whole page of the Times and the Morning Chronicles of July 23rd. Magdalene gave evidence on her brother’s behalf.

—

So what might Magdalene have seen when not following the antics of her wayward sister-in-law? Comparing it with a modern guidebook’s ‘must sees’ Planta reveals both similarities and some obvious and less obvious differences. Magdalene’s Paris had no Eiffel Tower, no Sacre Coeur, Pompidou Centre or Arc de Triomphe and the entrance to the Louvre looked very different.

But two sights she could have seen are still on today’s tourist list, The Catacombs and The Jardin des Plantes Menagerie. These are well described in Planta; as of course is the Palace de Versailles.

Interesting snippets from these will be in Part 2 of this Library Story later this month!

++++++++++

30-May-21 BOOKMARK TO CHOLERA

The Duff House Dunimarle Library was a family library, collected by several generations; and most importantly it was clearly used by the family members, and not just a set of books for show. This can be readily seen from the sketches and hard-writing found in various books, but also from the other items found within them, presumably used as bookmarks.

One of these seems quite innocuous, but serves as an example of how a small reference can lead a researcher down an interesting path.

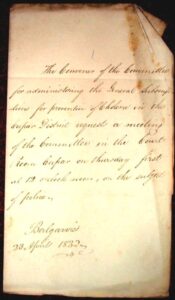

Duff House Library reference 236 is an 1830 copy of John Burke’s “A general and heraldic dictionary of the peerage and baronetage of the British Empire”; this is the third edition now of course a well known reference work. Within the pages of the Duff House copy is a handwritten letter:

“The Convener of the Committee for administering the General Subscription for prevention of Cholera in the Cupar District requests a meeting of the Committee in the Court Room Cupar on Thursday first at 12 o’clock noon, on the subject of police.

Balgarvie

23rd April 1832”

The signature is just initials and is not clearly decipherable.

Balgarvie House was just outside the town of Cupar, and it’s occupant at the time was believed to be Major General Webster – a rank that seems to fit with the title of Convener.

But the references within the letter to Cholera, and to the police, perhaps need explanation.

— — —

Cholera was first identified in Bengal in about 1813, but it did not spread to Europe for several years. Medical science was of course not as developed as it is today, and the causes of cholera – and what made it so contagious – were not understood.

Today we know that cholera is an infectious gastroenteritis bacterial disease transmitted from human to human by ingesting contaminated water or food. The bacteria produces a toxin that acts on the lining of the small intestines to induce massive diarrhoea. In its most severe forms in the 19th century, cholera was one of the most rapidly fatal diseases known and infected patients could die within three hours if treatment was not provided. More commonly death occurred after 18 hours to several days without therapy. Cholera spread quickly through germ-infected bedding or personal touch contact with infected victims. It was one of the most feared diseases of the nineteenth century, perhaps not least because the mortality rate of those that caught it was 50%; the newspapers often referred to the disease as being “virulently contagious”. By the end of the 1832 outbreak the cholera death toll in Scotland was about 10,000.

Once the disease became prevalent in north west Europe, the UK Board of Health at the time ordered that all ships arriving from the continent should be quarantined for 10 days before being inspected by a public health official. For whatever reason the officials in Sunderland didn’t apply this, and some infected sailors passed it to the local population in October 1831. From there it started to spread north and south.

The first case reported in Banff and Macduff was 30th July 1832 (according to the Annals of Banff, Mr Robert Barron of Macduff).

The Edinburgh Journal of 25th February 1832 provides an article that clearly states that “dirty” locations where people of “intemperate habits” tend to live, are most at risk. It is of course now known that it is passed on in dirty water or contaminated food and therefore can – and did – affect any person, but it wasn’t until 1855 – after a second cholera wave in 1848) that Glasgow became the first city in the UK to have a proper clean water supply and started building miles of sewers.

Until then the government issued guidelines about cholera. A Scottish one reads:

“Preventives

- Be clean in your person. Wear flannels next the skin.

- Keep the bowels well defended from cold, and never sit down with wet or cold feet.

- Abstain from small beer, and use spiritous liquours very moderately.

- Use no water that is not pure.

- The use of strong broth and butcher meat is salutary.

- Avoid raw vegetables, and boil well what you eat.

- Do not go out in the morning without breaking your fast.

- Avoid getting wet, or going out at night.

- Avoid also large towns, infected places, and public houses.

- Piggeries, Dunghills, and Cess-pools ought to be at some distance and frequently cleaned.

- Let the house be regularly ventilated, and well swept. When you wash it, choose a sunny day, and do it in the morning, so that there may be no damp when you shut up at night. Keep your doors dry.

Symptoms and treatment

Cholera generally begins with giddiness, languour, and uneasiness in the bowels, accompanied by looseness more or less. When such symptoms appear, no time ought to be lost in sending for medical advice – but in the mean time, 30 drops of Laudanum, and 3 teaspoonfuls of Castor Oil may be taken in a little hot brandy and water. Go to bed immediately, and keep yourself warm. Heated bricks or hot bottles may be applied, or bags of hot bran or salt. Place a mustard blister on the stomach. Let your drink consist of warm barley-water in small portions. Cold water is dangerous, and Salts must on no account be taken.

Should the Castor Oil &c be thrown up, take 30 drops of plain Laudanum.

Families ought to provide themselves with Laudanum and the other articles, as all depends on taking the disease at the first.

18th February 1832.”

— — —

The reference to police is also relevant. Further south, near Glasgow, in March 1832, records that a Constable was hired “to patrol the road to keep strangers out”. And then further, roads had manned barriers:

“At the Schooolhouse, met this day the members of the Committee of health, and appointed Mr Gibson & Mr Willm Killoch to employ and station a Constable at Walkinshaw Bridge to prevent beggars & unlicensed hawkers from passing out from Paisley. Mr Lockhart & James Snodgrass to arrange with the toll keeper at Inchinnan Bridge so as to prevent vagrants from getting into the Parish by that quarter.”

So by April, further north at Cupar, it seems that the local board were about to discuss doing the same sort of thing to try to keep the disease out. They had already had at least one case, and had burnt all his belongings and his lodgings!

— — —

One little letter, left inadvertently in a book used for another purpose, has led to insights into a piece of history and the actions government and local authorities took within a pandemic.

++++++++++

20-Apr-21 TAKE 5 OUNCES – how a Dunimarle recipe ends up in the Times

“Orange Pudding